African-Americans have been monumental — and often controversial — forces in the political realm since Reconstruction. Americans are hip to Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, Rosa Parks and Shirley Chisholm. But these weren’t the only people calling for sociopolitical change and advocating for justice. Black history is American history. So here are six lesser-known black politicians who broke barriers, fought for racial equality and played significant roles in constructing U.S. policy:

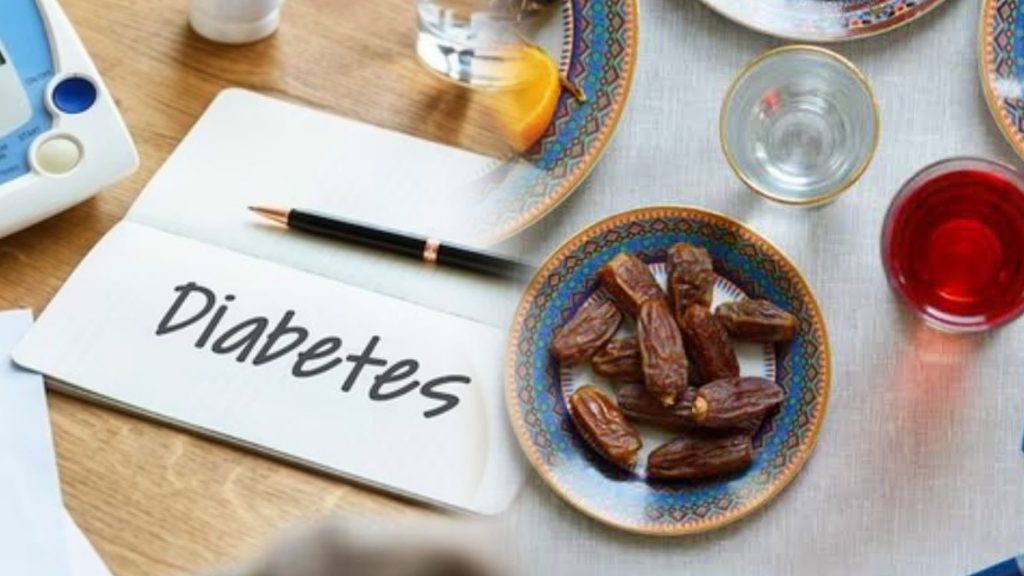

Robert Smalls

Robert Smalls MPI via Getty Images Robert Smalls, born into slavery in 1839, was elected to the South Carolina House of Representatives at the dawn of the Reconstruction era. A staunch advocate for African-American voting rights, Smalls proposed resolutions at the 1868 South Carolina Constitutional Convention that protected black voters and pushed the state to create the nation’s first public school system. Smalls represented South Carolina in the U.S. House of Representatives by serving in the 44th, 45th, 47th, 48th and 49th Congresses.

During his five congressional terms, Smalls continued to fight for black political representation and participation in politics as a member of the Republican Party. In 1895, Smalls refused to sign an amendment to the South Carolina state Constitution that essentially revoked the voting rights given to blacks in the 1868 constitutional rewrite, laying the foundation for Jim Crow laws in the state.

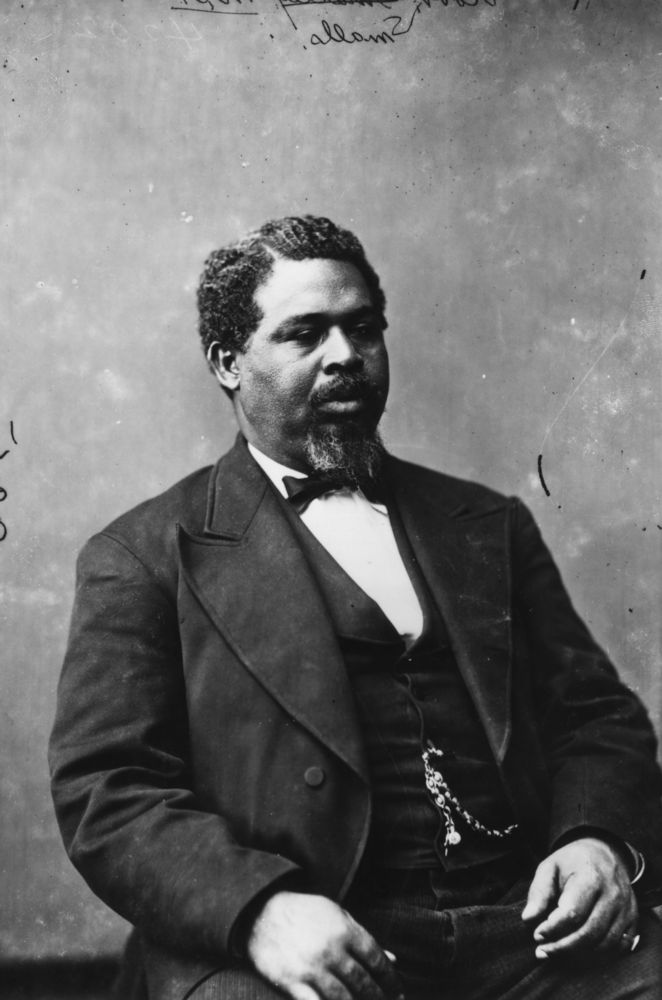

George Edwin Taylor Murphy

George Edwin Taylor was America’s first African-American presidential candidate. In 1891, he changed his party affiliation from Republican to Democrat in an attempt to reform the party’s ideals. When this endeavor failed, Taylor joined the National Liberty Party — a political group created by and for black Americans.

He ran on behalf of the party in the 1904 presidential election, but his campaign attracted little attention. Taylor’s platform, however, is worth noting. He called for universal suffrage for all races; federal protection of citizens’ rights; pensions for all former slaves; and government ownership of public transportation to ensure that facilities, though separate, would be equal. Perhaps the most profound aspect of Taylor’s platform was his goal to implement federal anti-lynching laws.

Keep in mind, the infamous St. Charles lynching took place in 1904, the same year that Taylor ran for president with the NLP. That event is thought by some to be the deadliest reported mass lynching in American history.

Alexis Herman

Before President Jimmy Carter appointed her to head the U.S. Department of Labor Women’s Bureau in 1977, Alexis Herman was working to improve employment opportunities for underprivileged kids in Mississippi. The drive to uplift underrepresented groups was a constant in Herman’s political career.

She challenged corporate America during her tenure in the Carter administration and convinced several large corporations to hire women into higher-level positions. In 1997, Herman became the first African-American secretary of labor under President Bill Clinton.

There, she facilitated the end of the UPS strike by mediating on behalf of the postal workers and expanded child labor standards with the Youth Opportunity Grants program — an initiative that increased educational and employment resources available to youth in high-poverty urban and rural areas.

Cynthia McKinney

Cynthia McKinney has been an outspoken and fearless figure since she first entered the world of politics. In the late 1980s, McKinney, then a Georgia state legislator, pressed the U.S. Justice Department to redraw district lines and create more majority-black congressional districts so that African-Americans would have more equitable representation in Congress.

In 1993, McKinney was the first African-American woman elected to represent Georgia in the U.S. House of Representatives. McKinney has taken a solid stance on multiple civil and human rights issues during her time in Congress. She was adamantly against the Hyde Amendment, a federal effort to eliminate Medicaid abortion coverage, which she called “nothing but a discriminatory policy against poor women, who happen to be disproportionately black.”

During the presidency of George W. Bush, McKinney introduced the Martin Luther King Records Act, demanding immediate release of all files pertaining to the life and assassination of King. She has also orchestrated panels discussing political attacks on black musicians.

Jane Bolin

Jane Bolin, America’s first black female judge, spent a significant portion of her career changing the judicial system by advocating for the rights of children, women and African-Americans. After her appointment in 1939, Bolin challenged — and changed — segregationist realities in the judicial system, such as color-based assignments for probation officials and segregated facilities in her hometown. She presided over juvenile crime, domestic violence, neglected children and adoption cases — all while opting out of wearing judicial robes so the children wouldn’t feel uncomfortable in her presence.

With Eleanor Roosevelt, Bolin also co-founded Wiltwyck School in upstate New York, a facility that aimed to eliminate juvenile crime.

Harold Washington

Harold Washington spent his time in office raging against Chicago’s Democratic political machine. During his time as an Illinois legislator (1965-1980), Washington backed fair-housing codes and the establishment of a statewide Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

When Washington graduated to the United States House of Representatives in 1981, he was staunchly against Reaganomics and spending cuts for social programs — measures Washington believed would hurt his constituents who relied heavily on federal assistance programs. He used his congressional seat to condemn proposals seeking to weaken affirmative action, and the Congressional Black Caucus also tapped Washington to oversee enhancements to the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Upon exiting Congress, Washington went on to become Chicago’s first black mayor. He died in 1987, just a few weeks into his second mayoral term. In honor of Washington’s legacy, the Chicago Tribune wrote that he gave “Chicagoans across the city a voice” and “set the tone for a new, more optimistic city and — even more important — turned its honeycomb of neighborhood groups into a force for improving the quality of local life.”